Despite advances in hiring practices and urban design, some common misconceptions continue to create barriers to employment and opportunities for people with low vision or blindness.

Learn from real people who want to set the record straight. Harrison, Abby, Jamal, Ingrid, Sarah, Lara and Zara are all young people with blindness or low vision and working in NSW. As part of our campaign for a Boundless World, the team are helping to reset common misconceptions and help remove boundaries for those with low vision or blindness.

Misconception 1: Low vision or blindness are rare

A common misconception is the belief that low vision or blindness affects only a small portion of the population. But in fact, there are more than 575,000 people with low vision or blindness in Australia, and this number is set to increase.

There are many types of low vision and people can experience low vision or blindness that may evolve over time. Conditions like macular degeneration or diabetic retinopathy can progressively get worse, leading to further vision loss.

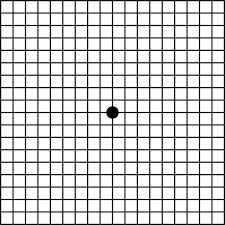

One of the most significant trends is the rise in refractive errors, particularly myopia (near-sightedness). A global rise in myopia, especially in urban environments, is thought to be due to factors like reduced time spent outdoors – however, research continues on its causes. The progression of myopia in children and young adults is also a growing concern. The World Health Organisation predicts that by 2050, half of the world will need glasses, while in Seoul, South Korea, myopia is thought to already affect 96.5 per cent of 19-year-old males.

Our ageing population is another factor contributing to the increasing rates of low vision. As people live longer, age-related conditions such as cataracts, macular degeneration, and diabetic retinopathy become more prevalent.

Is low vision or blindness preventable?

“In some cases it is,” Sarah says. “So, it’s always good to have your eyes checked. That being said, a lot of people are just born blind or with low vision. I was born with low vision. Mine isn’t correctable and it wasn’t preventable. And I’m totally fine with that.”

Misconception 2: You can’t live an independent life with blindness

Many people with low vision or blindness live independently, lead active lives and use a variety of tools and techniques that allow them to navigate the world safely and confidently.

“I live by myself in a studio apartment,” Jamal says. “I cook for myself. I pay my bills all myself. So yeah, independence is totally possible. A lot of blind people are living independently without any issues.”

Mobility training, particularly through orientation and mobility (O&M) instructors, equips people with the techniques they need to travel independently.

“We do get trained by orientation and mobility specialists as well as Guide Dog mobility instructors to navigate with our cane or our guide dog or no aid at all,” says Ingrid. “So if we’re moving happily along, we probably don’t need any help. But if you want to ask, always say hello first and just be polite about it.”

Using a white cane, for example, helps detect obstacles, changes in elevation, or transitions between different types of surfaces. This skill isn’t just about avoiding barriers, it’s about building spatial awareness to then feel confident in new environments and be empowered to make choices about where and how to travel.

Misconception 3: Dogs can only be trained to support people with low vision or blindness

For people with low vision or blindness, Guide Dogs are invaluable companions, providing assistance with navigating environments, avoiding obstacles, and crossing streets.

“If you struggle particularly with things like cafes, outdoor cafe settings, or if you can see during the day and it’s more tricky at night, that might be a good case where you can get a Guide Dog because they do make general navigation a lot easier,” Abby says.

But not just anyone is eligible to receive a Guide Dog. The selection process involves assessing the individual’s specific needs, abilities, and lifestyle. The individual must be able to manage the responsibilities of caring for a Guide Dog, which includes feeding, grooming, and regular exercise.

“You have to look after it,” says Jamal, a stand-up comic with blindness. “I mean, obviously, it’s a dog. You’ve got to feed it, brush it, play with it and walk it every day.”

Puppies can also be trained as Assistance Dogs or Therapy Dogs. Therapy Dogs can be a calming presence for those with all kinds of conditions and abilities. Some people may experience heightened anxiety or sensory overload when navigating crowded spaces, and a guide dog can help mitigate these challenges by providing a grounding presence and acting as a stabilising force.

Misconception 4: People with blindness or low vision can’t work regular jobs

People with low vision or blindness can and do work across a wide range of industries. In recent years, advancements in technology have dramatically increased the opportunities available to individuals with low vision or blindness. The workplace has also become more inclusive. Many companies and organisations now have diversity and inclusion policies that specifically recognise the needs of those with low vision or blindness.

However, significant barriers continue to exist, but these aren’t due to a lack of ability, but negative social biases.

“It’s quite hard to get a regular sort of full time or even part-time job as a person with blindness,” says Jamal. “You have to deal with a lot of negative perceptions about people with blindness.”

It’s important to note that individuals with low vision or blindness often undergo specific training to equip them with the skills needed for employment. This might involve using assistive devices effectively, while government programs like Job Access help employees and employers access adaptive technology at no cost.

Misconception 5: All people with low vision or blindness use braille

While many people with low vision or blindness use braille and recognise its importance for teaching children literacy, the number of Braille users has decreased significantly in recent years.

Today, only about ten percent of those with low vision or blindness can read it fluently.

“Unfortunately, there aren’t a lot of Braille readers,” Jamal says, “Whether that be due to lack of resourcing during education or people losing their sight later on in life and thinking that they’re not going to be able to learn Braille.

“I learned Braille later on in life. It’s made life a lot easier for me. It’s helped my independence quite a lot, especially in the kitchen, through labelling the things that I use in the pantry and whatever else.”

You might also like

Ready to continue?

Seems like you have filled this form earlier. Let’s pick up where you left off.